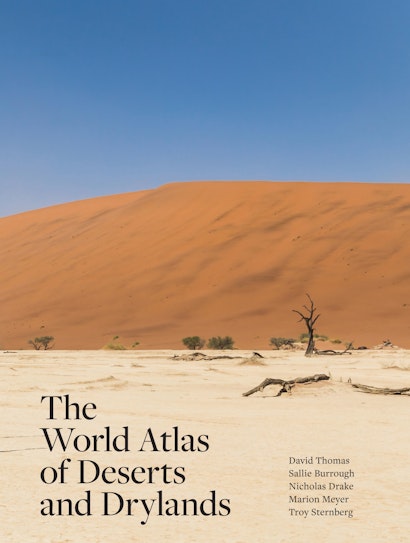

Deserts and drylands account for more than 40 percent of land on our planet. Characterized by a lack of water and extreme temperatures, they are the result of atmospheric stability, large landmass characteristics, rain shadows, and cold ocean currents. They appear harsh and hostile, but deserts and drylands are also exceptionally beautiful environments. Desert ecosystems often teem with diverse forms of life that exhibit astonishing ingenuity in the face of such forbidding conditions. The World Atlas of Deserts and Drylands takes readers on a guided tour of some of the most awe-inspiring desert environments on Earth, explaining their environmental and ecological dynamics and describing the techniques used to categorize and map them.

What is the big idea behind this atlas?

DT: Humans live in every corner of the earth, but we often think of deserts as mysterious, empty places that are difficult to survive in and difficult to get to. Sure, they can be challenging at many levels to humans, but they are also very diverse and are the center of many wonderful life-form adaptations and beautiful landscapes. The big idea of the book is to literally bring the complexity of deserts to the table, to allow these fascinating places—found on every continent and beyond our planet too—to be explored visually and through words.

Do deserts matter a great deal—and what are drylands anyway?

DT: People are often surprised when I say that over 40% of the earth’s land surface has an annual water deficit. This includes the most extreme desert areas, such as in parts of Namibia and Chile where it almost never ever rains, but also embraces huge swathes of land where there are varying degrees of water absence- including most of the western half of North America, large tracts of Africa and even southern Europe. These are the drylands—40% plus of the earth where currently around 1 in 3 people live. So at a range of levels, deserts and drylands really do matter.

How did you put the atlas together, and what are the roles of the others involved with the project?

DT: Deserts and drylands are such fascinatingly complex and diverse environments that, even though I have been researching, living and breathing them for over 40 years, I could never pretend to be expert in either every desert or every aspect of drylands. My experiences are deepest in Africa, as well as in Arabia and India, but I have only relatively briefly visited and researched in some other dryland regions such as central and eastern Asia and in South America. So I assembled a team of experts to complement what I know—colleagues who have also spent careers researching and wondering at these magnificent places. So Marion brought to the book a lifetime of research into plant and animal life of deserts, and Nick delivered on his fascination with how deserts came to be mapped and interpreted from ancient times to the 21st century, as well as his deep interest in the Sahara. Sallie came with her field- and lab- gained expertise in ancient desert responses to climate change and their early peoples, and Troy brought a deep knowledge of Asia’s incredible deserts that are for those of us from the west often the most mysterious and inaccessible. I felt that together this provided a dream team best able to convey the majesty, complexity and diversity of deserts and drylands. Importantly, I have worked before with them all, so felt that once I had built a framework for the book, we collectively had the capacity to create a whole that was greater than the sum of our individual desert parts!

You often speak of diversity in deserts and drylands- how does the book capture this?

DT: Yes, there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ desert—whatever the movies, TV and literature might make you think. And just as I really love sand dunes, they are but a small part of what these regions encapsulate. Deserts are hot—but can also be cold. They can be stupendously dry, but can also experience extreme wetness, while many dryland areas have regular seasonal cycles of (limited) rain and long dry periods. Some desert areas are extremely geologically stable, allowing processes and adaptations to evolve over long time frames, while others are just the opposite- subject to significant and regular tectonic disturbances. Significantly, we can add to this that the one overarching defining characteristic—a tendency to dryness, can be the result of a diverse set of environmental and atmospheric factors. So a big task at the outset was how to organise the book- and how to do so in a way that generates something different that hasn’t been done before. So early on when I was planning the atlas, the easy option, to arrange by continent, went out of the window, and I thought, lets do it by what causes dryness, and then look at what the consequences of these differences are for landscapes, ecologies and people. So I think the reader will be pleasantly surprised at the different organisational angle that lies at the heart of the atlas. I am also a very visual person, I love art and the huge vistas that deserts offer, so a book that is focussed on meaningful text AND a huge amount of diverse and beautiful illustrations seemed like the perfect way to capture these magnificent spaces and places.

There is so much concern at the moment about current environmental changes—is there something positive to say about desert futures?

DT: I first went to a desert—the Kalahari—to investigate its long-term environmental history and what drove the changes represented in its sediments and landscapes. My work soon extended to include understanding how people had, and still do, adapt to diversity, to uncertainty and to change. Since then, I have seen the predictability of rains in the short-wet season change, plant patterns and animal movements change, and people adapt. It’s tough, but what I have learned is just how robust and resilient people—and environments—can sometimes be, as well as how our early ancestors adapted to deserts. Adaptation though gets tougher as extreme events- drought, floods, heatwaves, rise in occurrence and magnitude. In the book we also cover aspects of negative human impacts in deserts and drylands—it would be shortsighted not to—including the US Dust Bowl period with its complex underpinnings—but we also flag and highlight some significant success stories and positives for the future—such as the energy that can be generated in deserts directly from the sun and the incredible adaptations animals have made and continue to make to harsh and changing desert conditions.

What is your takeaway message for readers of the atlas?

DT: I really hope—actually I really think—you will come away from the book wowed by the majesty and complexity of deserts and drylands, awed by their diversity and beauty, and impressed by how life forms, including our species, have adapted to the challenges that deserts and drylands present.

David Thomas is Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford, and an Honorary Professor at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. His many books include The Kalahari Environment, Desertification: Exploding the myth, Arid Zone Geomorphology and Sustainable Livelihoods in Kalahari Environments. He lives in rural Oxfordshire, from where he is planning his next desert trip.